The Hardest Part of Making A New Material: Actually Making It...

November 3, 2025

Publications

Materials are the building blocks of modern industry. Without rare earth magnets we wouldn’t have EVs, wind turbines, hard disks, or most heavy industrial machinery. Without Si chips and gate oxides we wouldn’t have air traffic control, or phones and laptops (and this white paper would be quite useless). Without Li-ion batteries we wouldn’t have portable pacemakers, drones, EVs, or phones. The list goes on: piezoelectrics (ultrasound, GPS, sonar), thermoelectrics (the Mars rover), silicon steel (power grids). Materials are beyond critical for modern economies, and new materials enable new technologies. Altrove uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) and automation to make material discovery up to 100× faster and cheaper.

The need for alternatives

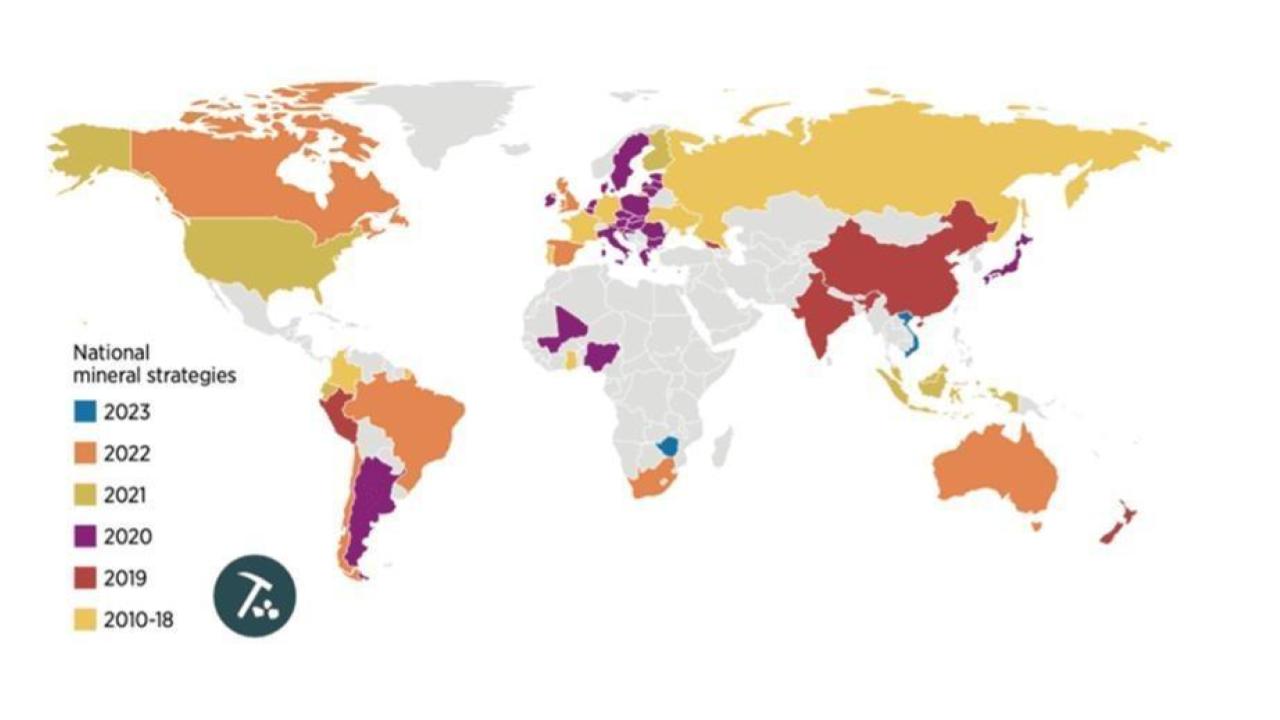

In the last decade, nearly every industrial economy has adopted a critical mineral strategy:

Figure 1: Year of adoption of critical mineral strategies across major world economies. Materials have become ever more critical with wider electrification and adoption of new technologies.

The reason, simply, is because our economies are so dependent on these critical materials that not having access to them is catastrophic. For industrial companies, having access to materials that enable their core business is essential; lose the material, lose the business.

AI for Materials Discovery

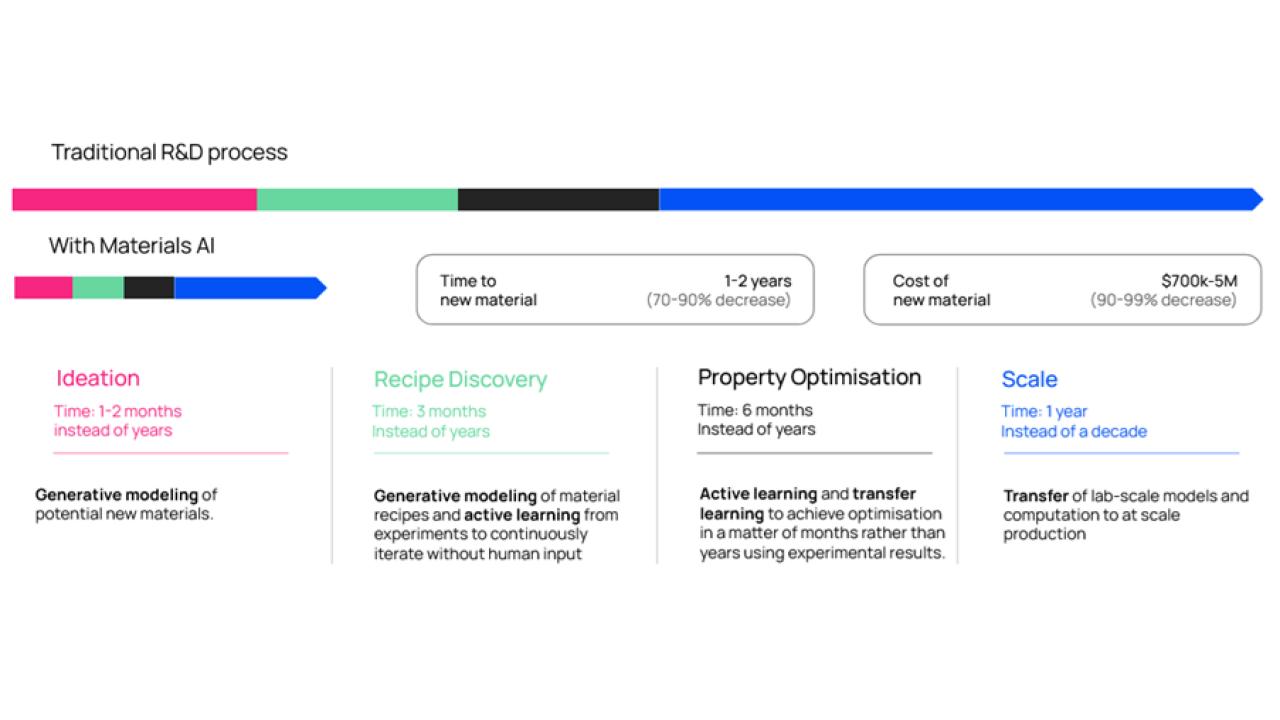

AI holds a simple promise for materials science: make a slow and random process (traditional R&D) fast, reliable, and cheap, while simultaneously unlocking immense value of new engineering applications. Today, materials R&D is still a human-driven (and human-limited) process that takes decades and $10s-100s of millions to bring a novel material to market. At Altrove, we do it in 2 years (to scale) and in under $1M:

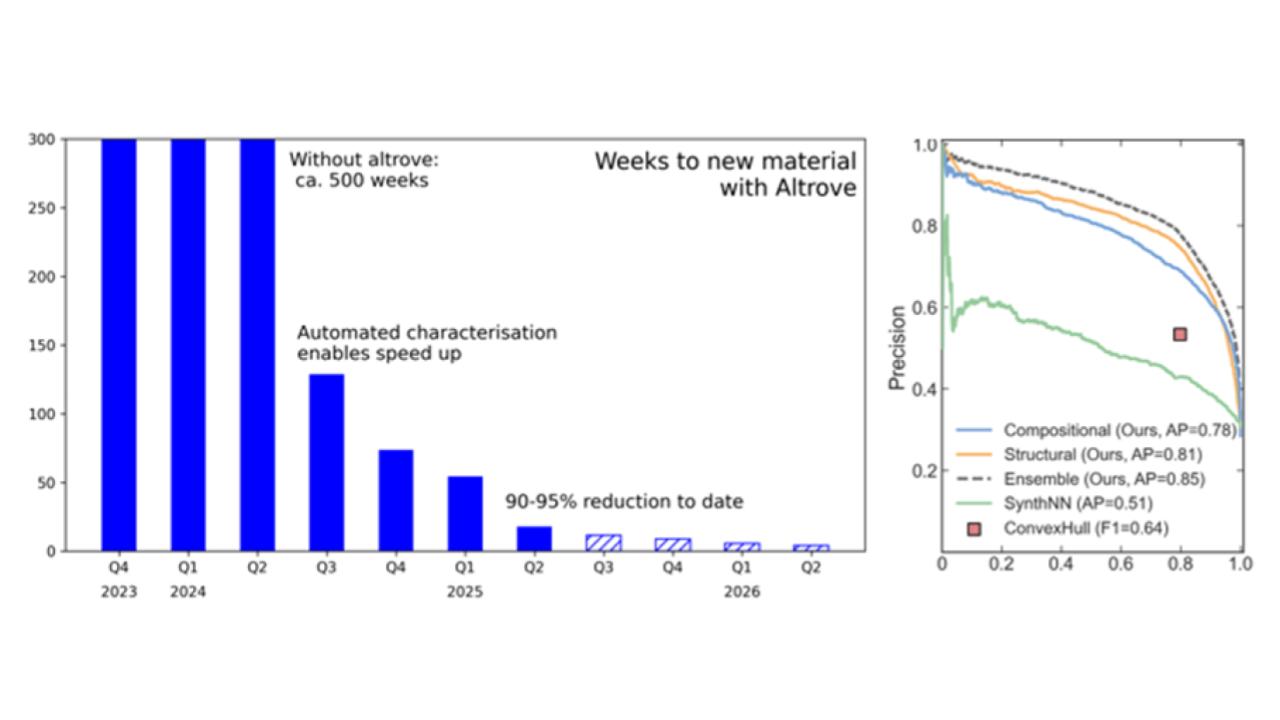

Figure 2: Altrove’s timeline for novel materials production and the potential AI for materials. Cost and time are both reduced by 90%, enabling much faster adoption of critical new technologies.

The Challenge

The question is how to unlock this potential upside. Let’s go through the difficulties of traditional R&D:

1. Uncertainty of Success

Materials R&D has historically been serendipitous. In 1986, Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Müller discovered LBCO (Lanthanum Barium Copper Oxide), a superconductor that would soon result in the YBCO (Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide), the highest temperature superconductor developed for industrial use. It was a stroke of serendipitous strategy, researching compounds with large polaronic effects and unusual phase transitions, and discovering a novel type of superconductor. Hundreds of researcher groups have aimed to better the result since, and none have succeeded. Nearly forty years of targeted research!

Technically, AI changes this. By rapid prediction of novel crystal structures (the arrangements of atoms that govern key material properties) and fast screening of millions of potential candidates, we can pre-predict which materials are likely to be interesting. This turns semi-random searching to focused targeted discovery.

However, experimental results are still not certain, as you are regularly predicting outliers and the error remains high.

At Altrove, this second problem is a problem of throughput. By making ourselves capable of running as many experiments as a hundred, or a thousand researchers and simultaneously learning from all of them, we remove the element of chance and enable novel technologies to be discovered at a fraction of the time and cost it used to take.

2. The Trouble with Synthesis

Making materials is hard. Really hard. You can have a perfect material that works in simulation, even in small-scale testing, but is nigh-impossible to manufacture in bulk.

SmFe12 has been promised as an improved rare earth magnet material for well over a decade, and even been validated as a thin film. The problem? Try to make bulk SmFe12 and you will fail. The material decomposes into other materials during processing, preventing industrial use. What might seem like the simple part, is in truth often the hardest,most time-consuming and expensive. Years are spent slowly improving recipes for making novel materials, and years cost money.

The technical problem is deeper. The thermodynamics of synthesis are extremely complex, and often poorly predicted by computational models (particularly at high temperatures necessary for synthesis). From a computational standpoint, while high data volumes (10-100M data points) exist for generative modelling, only 50-100k data points exist for synthesis. The data quality is poor, filled with a large variety of synthesis methods, partially complete recipes, and only success data (and failure data is much more important!). For an individual system, only tens or at most hundreds of data points exist. This is therefore a regime of active, representation, and transfer learning, rather than pure ML/AI. A lab is also a must. Both enable rapid searching with large numbers of high-fidelity data for the specific system.

3. Optimisation is the other half of the challenge

You would be inclined to think that once you get past the synthesis, things would get easier. However, optimisation of the synthesis recipe (to get the optimal properties of the material) is just as hard and as time-consuming. The properties of optimally doped BaTiO3 (BTO) are between 2x and 5x of the pure material (even after the pure material is optimised in recipe). The precise additions of Ca, Zr, Co and other elements change the properties dramatically. It seems simple enough, just add the right amount of each element! However, the problem is combinatorial, 6 potential dopants hundreds of millions of potential compositions, and finding the optimal one is extremely time-consuming.

Technically, the challenge is of two parts. Again, one is of active, representation, and transfer learning. Data points are very few (100-1000s) and often from a mixture of different sources, carrying different systematic errors. The key goal is to find the point of optimum performance, while minimizing the number of experiments to get there. High experimental throughput is a must, or this process will quickly end up taking years. The second, more insidious challenge is disorder. In doped and alloyed materials, atoms of one element occupy sites of other atoms randomly; the structure is disordered.

This is a problem due to DFT (density functional theory). DFT is a way to simulate the properties of a material given its arrangement of atoms and is the cornerstone of materials simulation and modelling. However, it cannot accommodate disorder.

Therefore, separate simulation frameworks are needed to evaluate the optimised versions of materials. That said, not all properties can subsequently be calculated. Computational materials science (and AI within it) remains poorly equipped to handle disorder, despite it being a cornerstone of material discovery.

4. Scale scale scale

All materials must be produceable at scale to be relevant in industry. Scaling up a material is a challenging and expensive process, but scaling up a novel processing method is triply so. Startups and innovators have a tendency to underestimate the complexities of scale. GaN (gallium nitride, 2014 Nobel Prize) which is the key component of modern blue (and therefore white) LEDs was identified as a key blue LED candidate and synthesized at lab scale in the 1960s, but it took until 1986 (with Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano) and 1989 (Shuji Nakamura) to achieve key breakthroughs in producing large samples and appropriate doping for electronics integration. It was these breakthroughs that would win the Nobel Prize.

Technically, at-scale optimisation is about porting methods from the lab-scale to industrial machinery, industrial lower-grade precursors, and higher condition variability. For rapid novel materials development, choice of manufacturing vertical and matching lab-scale processes to industrial processes are the best tools that can be built in at lab-scale. Using a specific small-scale fluid process to produce a compound is likely to result in failure at a later stage, as opposed to working with powder processing at lab-scale. Efficient use of human expertise and transfer learning are likely the most efficient tools for this stage.

The outlier problem

Industrial materials are outliers. It’s not a coincidence that finding alternatives to Nd-Fe-B magnets and lead-based PZT (lead zirconium titanate) piezoelectrics is difficult. After all, they were industrialised precisely because they had exceptional properties. The technical problem is then about searching for outliers. This has a significant impact on the choice of potential new material candidates. We must keep identifying potential outliers for materials based on current knowledge. This gives greater value to simulation tools for identification, as they are expected to be more capable outside of the training data. In addition, it means we need to be able to distinguish outliers from statistical errors, which inherently requires high testing capability or very precise models. For us at Altrove, high experimental throughput is again a way to solve this problem. We can spend time on statistical errors if it also means we hit the outliers.

Altrove’s Process – the solution

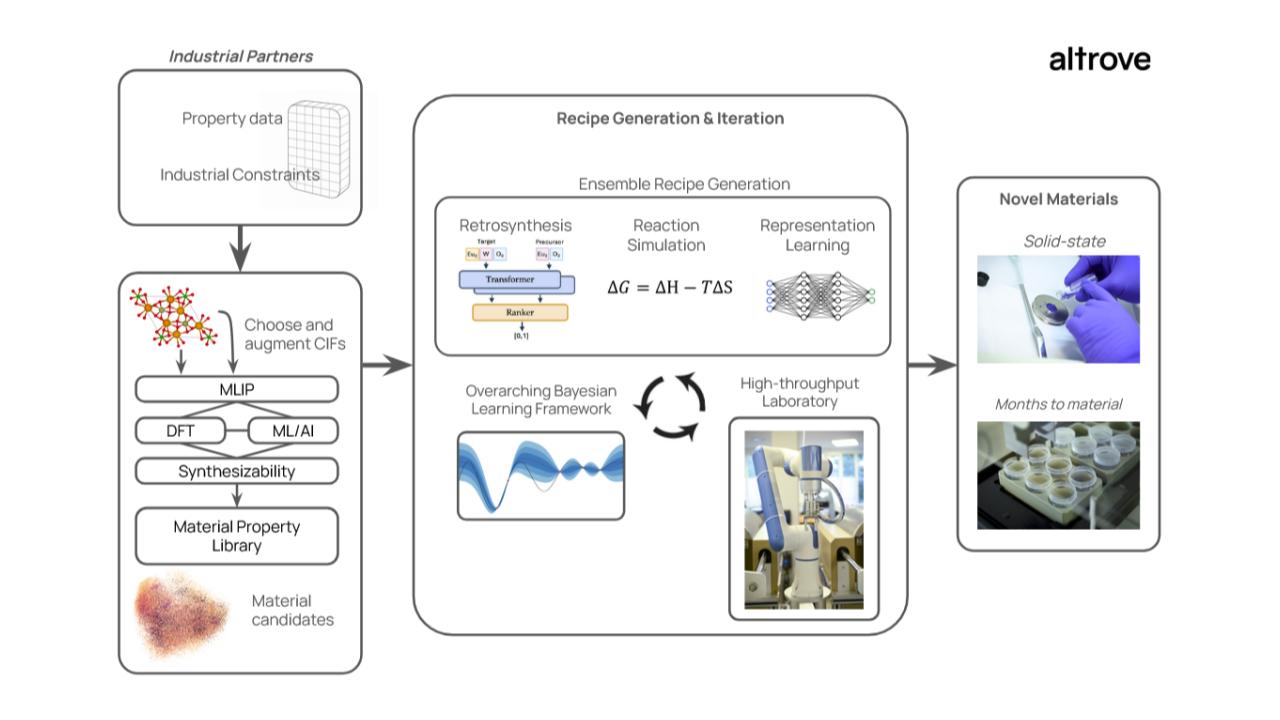

Altrove builds new materials at a fraction of the time and cost of traditional R&D methods. We do this by:

Selecting novel materials out of millions of possibilities using AI, machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs), and DFT.

Generating plausible synthesis recipes using in-house reaction modelling.

Using our automated lab to do hundreds of experiments per week.

Automatically analysing and characterizing the results and feeding back to our recipe prediction models.

This enables us to continuously build novel materials and, with high real-life throughput, reduce the impact of computational errors.

Figure 3: Altrove’s process for novel materials discovery. Commercial specifications are used to select potential materials. These materials are then synthesized and optimized using high-throughput experimentation and an overarching optimization framework.

Selection, not Generation

Generating novel structures is vital to have a large pool of potential novel materials, but it is only the first step in bringing a new material to market. For each novel structure, the most important question to ask is “Is this material interesting?”. Traditional methods like DFT are simply not suited to screen millions of structure, being far too expensive in terms of compute and time. At Altrove we employ a multimodal materials screening pipeline, combining the precision of DFT with the speed of GPU-accelerated MLIPs. The two provide both speed and precision for the calculation of key material properties. The result? Millions of materials are screened for properties (band structure, magnetisation, thermodynamic stability). The best are subsequently funnelled through the more expensive DFT and MD simulations to verify their properties; speed and precision. Our selection pipeline is driven ultimately by materials expertise, deep domain knowledge of materials specialists combined with computational tools. The most important part: they work.

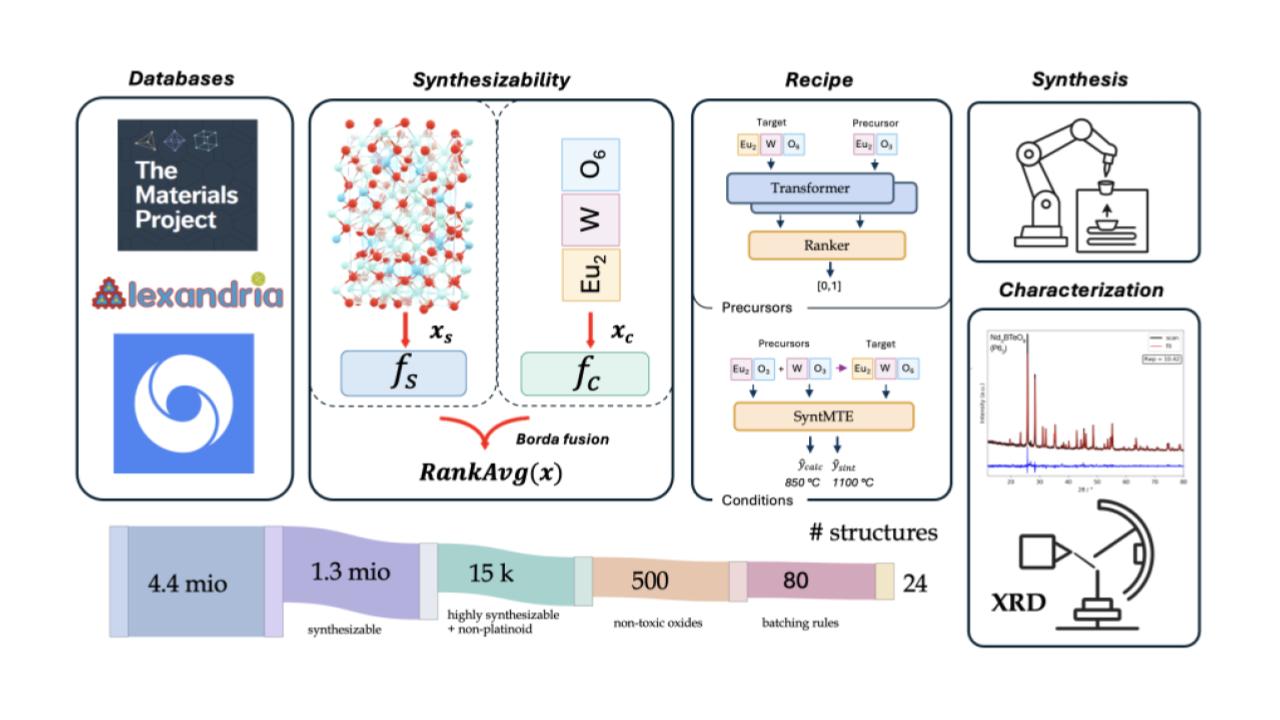

Synthesizability

Not all predicted materials are created equal. We must find those that are interesting and possible to synthesise. It’s typical to judge the likelihood of a material existing using DFT stability. DFT stability tells us if the material is the most favourable arrangement of atoms, but this is done at absolute zero temperature (0 K). 0 K energy prediction provides guidance but isn’t accurate to materials that are synthesized at high temperatures.

Many key materials technologies (that are typically stabilised at high temperatures), are metastable (unstable but very close to stable) at 0 K. For example, virtually all key magnet technologies (Nd2Fe14B, SrFe12O19, SmCo5) are metastable in simulation. As the number of predicted structures increases, it becomes increasingly more difficult to judge which metastable phases are plausible. For example, the Materials Project lists 21 silica (SiO2) structures that are plausibly stable by being within 0.01 eV of the convex hull (as of August 2025). The second most common phase of naturally occurring SiO2, cristobalite (β-quartz), is not among these 21. How do you best classify cristobalite as synthesizable?

It is therefore vital to judge the ‘synthesizability’ of potential materials, irrespective of their DFT-calculated stability. At Altrove, we have developed and experimentally validated a state-of-the-art synthesizability metric that can successfully judged whether materials are likely to be synthesizable or not (see Figure 4). We showcased and validated it in our recent publication, showcasing both how predicting synthesizability is vital for ensuring efficient experimentation, and how you can only judge some algorithms once you test them in the real world:

Figure 4: Altrove’s state-of-the-art synthesizability pipeline. Using a mixture of a structural and compositional model, we are able to highly accurately identify and subsequently synthesize novel materials. This means that lab throughput is used on experiments that matter, rather than chasing compounds that will never be synthesized.

Recipe Generation & Iteration

Science should not be human-limited. To speed up material discovery, we believe that human input is still necessary. The most important part is that it should not be the limiting factor. That means that ML and AI have to generate and iterate on synthesis recipes. In addition, they can search and use the entire corpus of academic publications and experimental data to propose plausible and varied recipes. Altrove combines several modelling and simulation methods, each adding a different layer of insight to the recipe-generation process. Each predict different types of synthesis recipes for a given material. The most important part is to combine these differing ‘information sources’ under an overarching framework.

Altrove uses an adaptive optimization framework to unify different data sources and guide experimentation efficiently for two main reasons. Firstly, data volume for recipes is highly limited (< 100k total, < 10k high quality) meaning that model architectures are limited by reaction data volume. Secondly, optimization frameworks are flexible, and has shown excellent performance in the biosciences for reaction optimization. The system integrates multiple data sources and continuously improves its predictions through experimental feedback, enabling flexible operation across different data sources. In addition, experimental results are smoothly incorporated into an optimization workflow. Ultimately, recipes are data-limited, which is why having access to high-throughput experimentation is especially important.

Benchmarks of Success

At Altrove, we have successfully synthesized novel materials over the last year. We’ve learned many lessons, but some of the key lessons are:

Computational algorithms that stay in the computational realm don’t work. Synthesis is exceedingly complex, and there are many failure points. Losses and computational benchmarks mean nothing if the algorithm does not function in the real world.

The tech stack is inevitably multi-modal. Different amounts of data for different tasks means that multiple model types are needed to efficiently succeed.

Domain expertise remains key. Effective use of domain expertise and human input remains a vital tool for AI for materials. Efficient deployment of it is complicated but vital. (AI systems remain nowhere near as smart as domain experts as of now!)

Figure 5: Left: Speed-up provided by Altrove’s automated materials discovery platform. By reducing the number of experiments needed to and increasing laboratory throughput by running 100+ experiments per week. Right: Synthesizability precision-recall curve developed by Altrove compared to state of the art.

Conclusion

At Altrove, we have built the world’s fastest method of creating novel materials using our high-throughput laboratory and AI algorithms. Still, we believe that many of the hardest problems for AI in materials discovery remain unsolved or only partially solved. We have an immense opportunity to solve these problems, namely:

How to accurately predict and estimate the properties disordered structures and materials

How to best generate complex but synthesizable crystal structures

How to consistently find novel outliers among predicted materials

How to guarantee and modelise scaling for novel materials

If you want to help redefine how the world invents new materials, get in touch at tech@altrove.ai.

Recommended Papers

Here’s a few papers to read further:

Merchant et al. "Scaling deep learning for materials discovery." Nature 624.7990 (2023)

Szymanski et al. "An autonomous laboratory for the accelerated synthesis of novel materials." Nature 624.7990 (2023)

McDermott et al. "A graph-based network for predicting chemical reaction pathways in solid-state materials synthesis." Nature communications 12.1 (2021): 3097.

Horton et al. "Accelerated data-driven materials science with the Materials Project." Nature Materials (2025): 1-11.

Negishi et al. "Continuous Uniqueness and Novelty Metrics for Generative Modeling of Inorganic Crystals." arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.12405 (2025).

Choi et al. "Synthesis-Aware Materials Redesign via Large Language Models." Journal of the American Chemical Society (2025).